Recent Articles

-

Christmas Sword Buying Guide 2025

Dec 03, 25 10:53 PM

Antique Samurai Swords: A Personal Journey in Japan

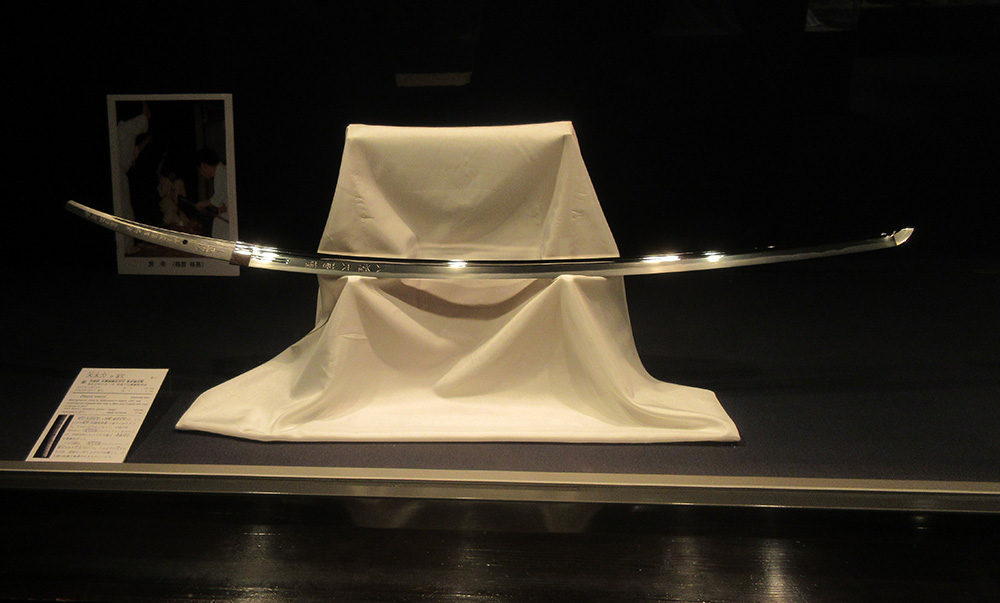

One of the Antique Samurai Swords I handled and examined closely - a 400 year old sword in Shirasaya made by the smith Kanemoto

One of the Antique Samurai Swords I handled and examined closely - a 400 year old sword in Shirasaya made by the smith KanemotoI always considered antique Samurai Swords to be well out of my league..

Until this trip to Japan in January 2020, I could count the number of genuine antique Nihonto (the term for live bladed Japanese swords actually made in Japan) on one hand.

But within the space of a few days, I had dramatically changed all that - getting special access to the "Sekikaji Denshokan" Museum at Seki city, a traditional Japanese forge and getting special access to more antique Samurai Swords than I could have ever hoped for - all thanks to a chance email out of the blue..

And from these experiences also came a new mission. For all was not well for the sword market in the land of the rising sun - and by chance and serendipity, I find myself in a position to actually make a difference, albeit a small one.

But I am getting ahead of myself. Let's start at the beginning..

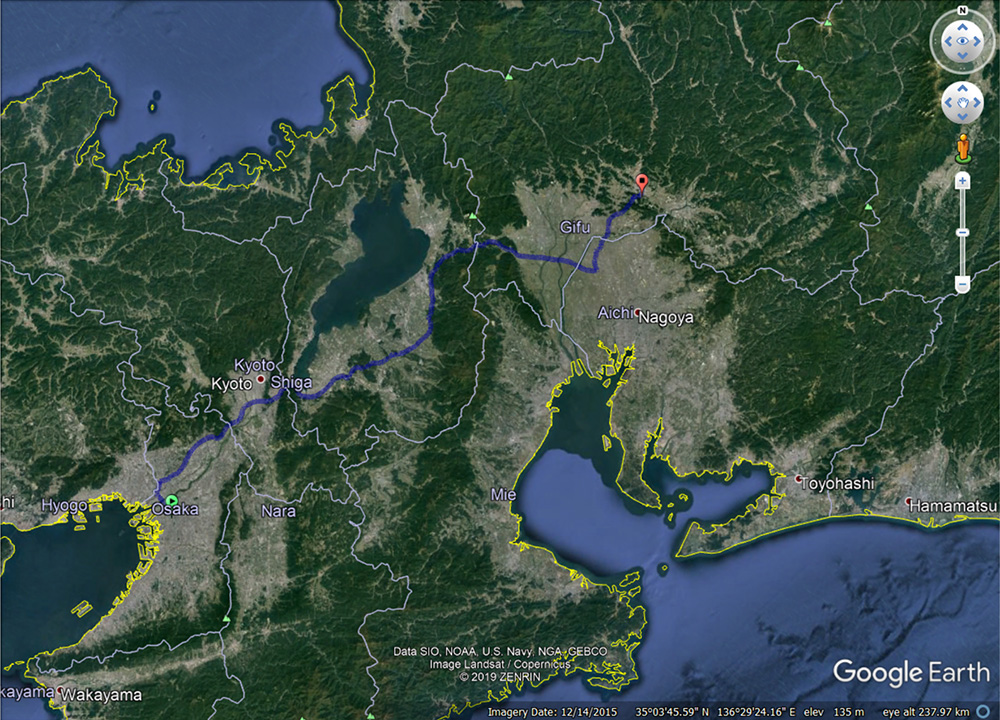

Japan's Blade Making Capital - Seki City

I am no stranger to Japan, having lived there for 7 years continuously and able to get by in the language and culture. With my daughter from a previous marriage living there, naturally I am still a frequent visitor - though mostly to the 'Kansai' area (which includes the old capital Kyoto, Nara, Osaka and Kobe) where by daughter currently lives.

When I lived there, I spent as much time as I could checking out antique Samurai Swords - but without the right contacts could never quite break through and get 'insider access' as I have at many other sword making centers around the world.

On the outside looking in - while I saw many blades in Japan, it was rare to be able to handle them

On the outside looking in - while I saw many blades in Japan, it was rare to be able to handle themIn hindsight I think my awe of genuine antique Nihonto and a feeling of inadequacy, based on having specialized in entry level functional replicas, held me back.

So when an email came out of the blue in late 2019 as I was planning my Christmas trip to Japan (a visit to snowy Hokkaido with my daughter) - it grabbed my attention..Was this the lead that I had been hoping for?

The email was from Chris Loeber, a long time resident of Ichinomiya in Aichi prefecture near Nagoya. The long and short of it was that he was a friend of a Japanese sword maker and was looking to sell off a large quantity of antique Samurai Swords..

Fast forward a few months to January 2020 and I set off from my base in Osaka to Nagoya via bullet train and met up with Chris for beers and Yakiniku BBQ beef near my business hotel.

A quick 50 minute ride on the Shinkansen Bullet Train and a side step from Nagoya and the adventure had started

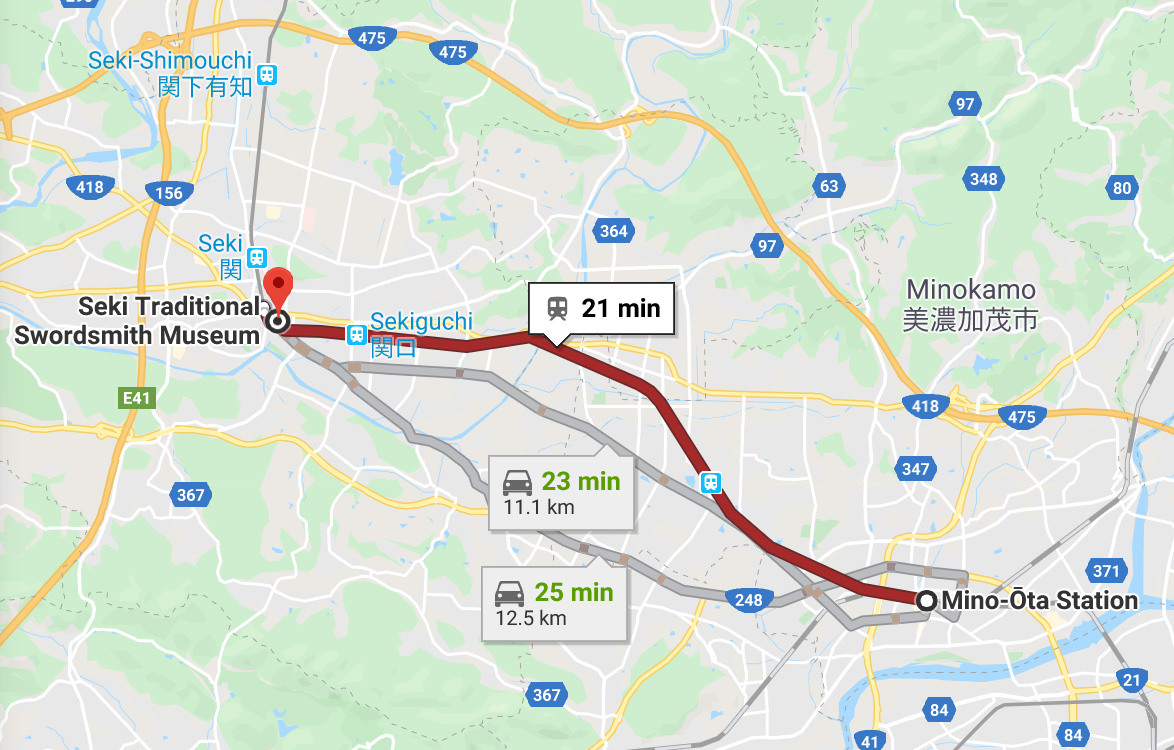

A quick 50 minute ride on the Shinkansen Bullet Train and a side step from Nagoya and the adventure had startedAccessing Seki City would be a little harder, as there is no nearby train station and the only way to get there is by bus or car. But while access may be a little inconvenient, it is well worth the effort and a 'must visit' for any Japanese sword enthusiast..

Directions to actual sword shops all throughout Seki City - a sword lovers paradise!

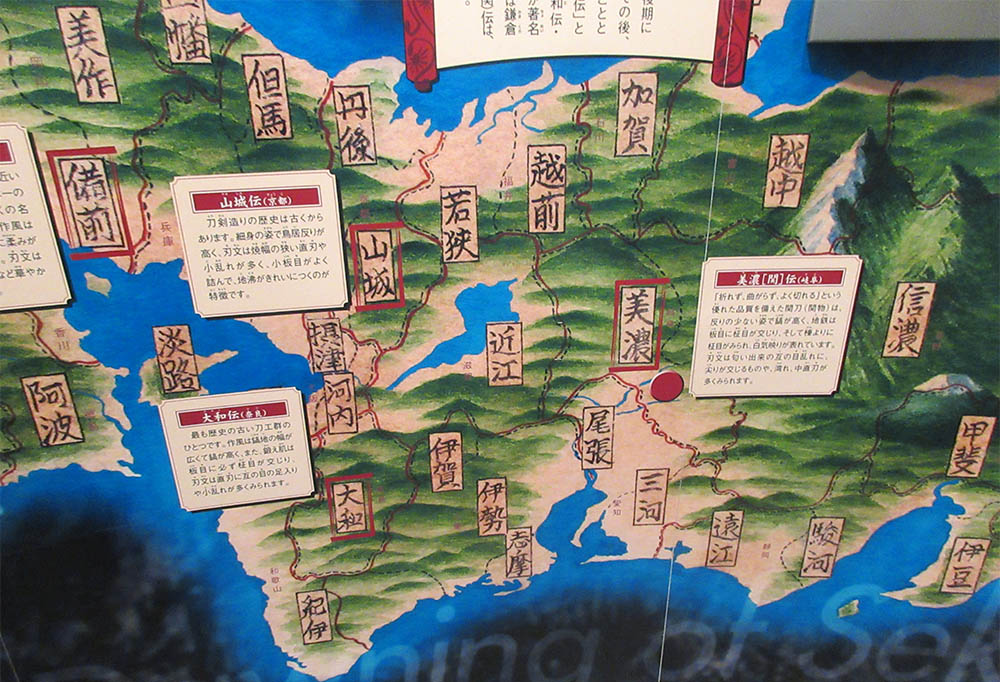

Directions to actual sword shops all throughout Seki City - a sword lovers paradise!Back in the day, Seki was one of four major sword production centers in Japan as shown on this map at the Seki Traditional Swordsmith Museum.

It also proved to be the most resilient. For while it was the last to join around 700 years ago, the other 3 are long gone and only Seki city continues on as the center of Knife and Sword production in Japan - the equivalent of Solingen in Germany or Longquan in China.

Over beers Chris and I got on well and started to draft out a plan for the next week.

But first, it was time to see some swords..

Handling Antique Samurai Swords

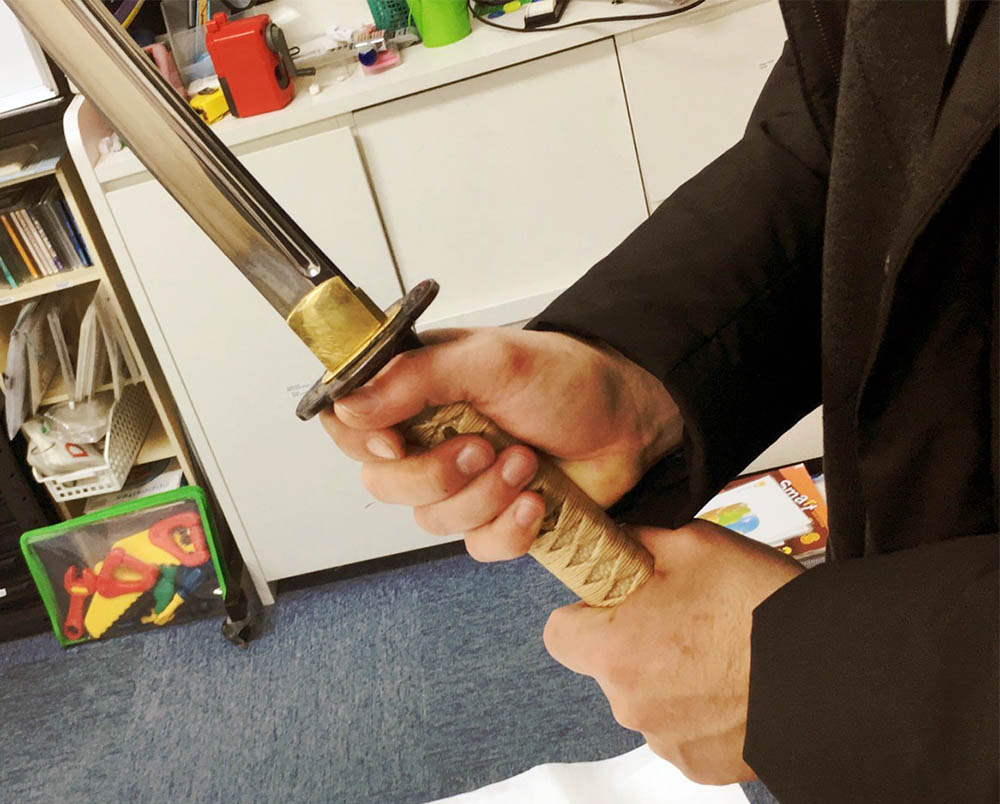

The next day, I met Chris at the school where he owns and has been running for the last decade and checked out a couple of the antiques first hand..

There is a complex set of rules surrounding how to handle antique Samurai Swords with respect and avoid causing any damage to blades that are hundreds of years old.

But for the average layperson, there are three golden rules to remember.

- When you draw the sword, you do so holding the sheathe with the tip facing away from you and draw it out in one smooth action, careful to avoid the blade's edge from touching any part of the sheathe (see the video above).

- When inspecting a blade, be careful to avoid breathing on it or touching it with your bare hands as the acid in your sweat and water condensation from your breath can both cause rust.

- When you hand the blade to someone else, face the edge towards yourself. Same principle as when you hand someone a pair of scissors.

Remember these rules and you will avoid the worst faux paus - most of the inspection you do should be visual - and trust me, it is very easy to literally lose yourself in the craftsmanship of genuine antique Samurai Swords..

Even if the polish does not reveal the 'hada' (the skin of the blade showing the subtle folded Tamahagane steel) - and most do not as - there is something truly otherworldly about holding in your hands a blade that once belonged to a proud Samurai family and wondering about it's past.

If only the swords could talk..

Indeed, this is one of the most fascinating things about an individual antique Nihonto. Each has its own story to tell, and as in most cases the sword is divorced from its owners with no records of its various owners through the centuries, only who made it. And in some cases, even who made it is not clear if the tang is unsigned.

Such blades are called 'Mumei' (no name) and while it may indicate a blade not quite up to the smiths standards, but still good enough to use, that is not always the case. The swords of the legendary sword maker Masamune are always unsigned, and such blades are priceless national treasures!

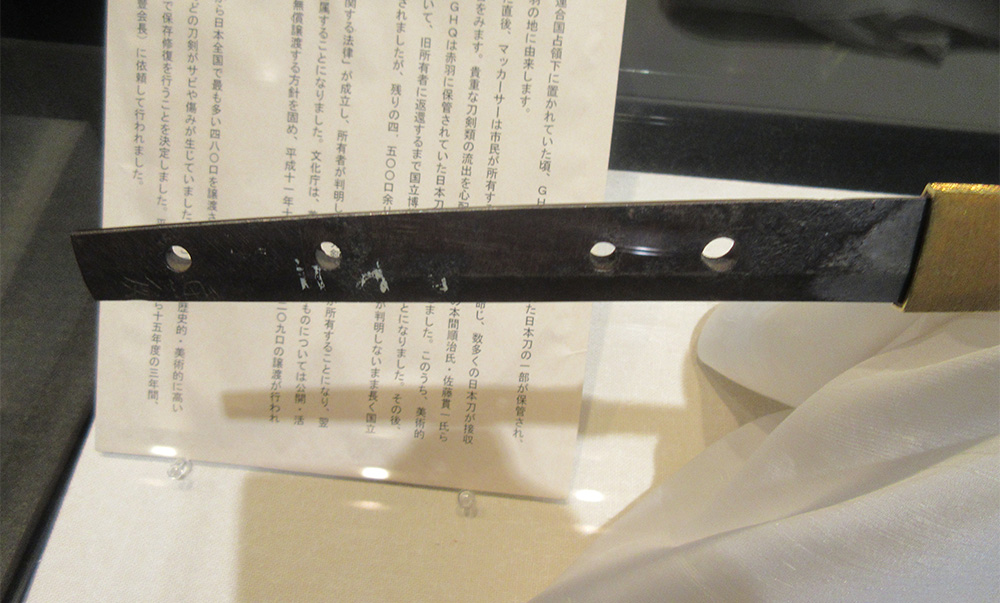

An unsigned 'Mumei' tang (top) compared to a standard signed Tang. The signature always appears on the same side of a sword - the side facing you when you place the blade with the tip to the right, curved side up. The other side typically has the date.

An unsigned 'Mumei' tang (top) compared to a standard signed Tang. The signature always appears on the same side of a sword - the side facing you when you place the blade with the tip to the right, curved side up. The other side typically has the date.But perhaps the most fascinating thing about antique Samurai Swords is that each sword hints at it's history and the times it may have been the only thing separating life from death..

Take for example one of the antique Samurai Swords I saw dated to the mid Edo period by Echizen Kanetane.

Stunning antique blade, but just below the hint of a very interesting encounter..

Stunning antique blade, but just below the hint of a very interesting encounter..The blade in this case is a distraction - the real story this sword only hints at, and is to be found not on the blade but forever marked into the sheathe - the saya. For the saya has on it three light but clear cuts that are unmistakably that inflicted by another sword, quite likely when the blade was still in its sheathe..

Three sword marks on the sheathe suggest a violent encounter..

Three sword marks on the sheathe suggest a violent encounter..As noted the cuts are not that deep, suggesting they were delivered at speed - and with three marks close together like this it is hard not to imagine a confrontation where a young hot headed Samurai tries to pick a fight with its more experienced and reserved owner..

Perhaps in a fit of rage as the more dignified Samurai ignored the taunts and provocation of his would be assailant, the young man lashed out with a series of cuts that were either blocked with the sheathed sword or, more likely, were strikes of provocation against the undrawn sword.. Essentially the Samurai equivalent of shoving someone in the chest before starting a fight in earnest.. (of which, incidentally, the word earnest translates to Japanese as 'Shinken' - the same word for live blade - meaning 'as earnest as a live bladed sword'..)

It is in the little details that the story of each Nihonto hints at if you look carefully - just enough to raise questions and imagine possible scenarios that can never really be verified. But this too is part of the appeal - the unending mystery that has you digging deeper into the particulars of Japanese history - and how close to history you feel when you hold or own one of these magnificent weapons..

A Visit to the Museum

One of the best places to both see antique Samurai swords, and understand how they were (and still are) made and just how much time and effort goes into each one, is of course the museum. In this case, the local museum serves as a hub for all the local Seki city sword makers, artisans, art dealers, scholars and custodians - and is one of the driving forces behind keeping the local tradition, the last of the four major sword centers in Japan, going into the uncertain future of the 21st century..

The first thing you are greeted with is a large recreation of three Tosho (master blacksmiths) beating the Wako steel, otherwise known as Tamahagane.

Did you know that the smiths clothing is what the Samurai wore under their Yoroi armor?

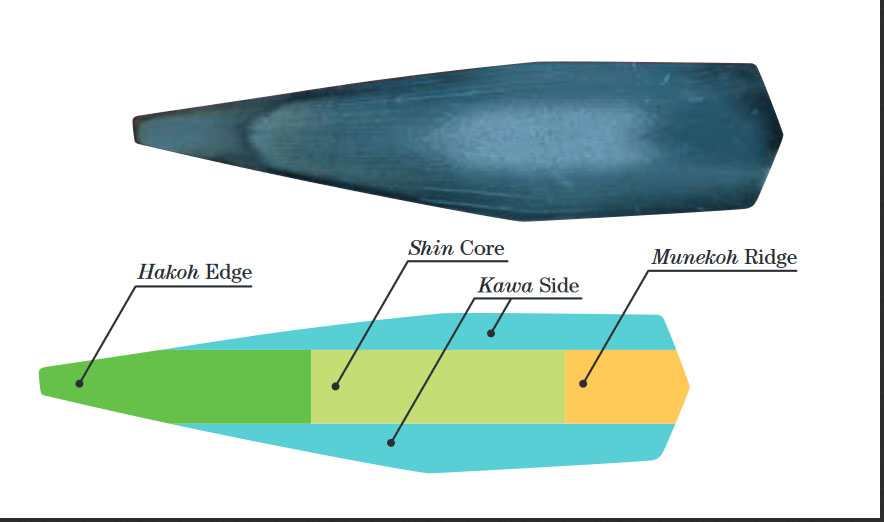

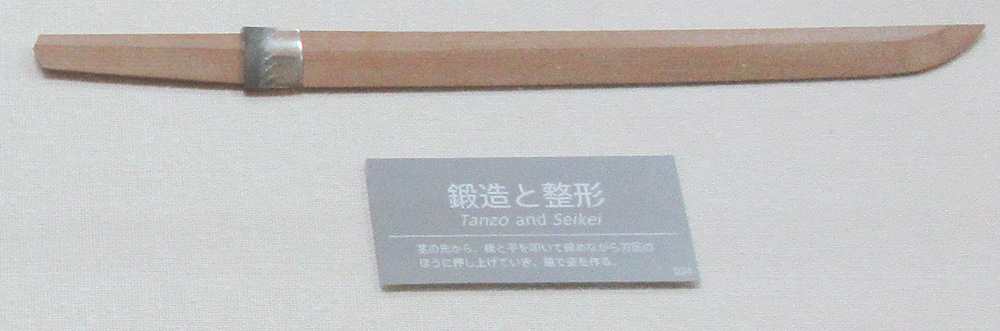

Did you know that the smiths clothing is what the Samurai wore under their Yoroi armor?Various techniques are used in the process of creating a Katana, always fusing together several

different distinct layers of hard and soft steel in time tested

configurations such as Kobuse or, the districts specialty, a complex lamination known as Shihouzume - resulting in a hard cutting edge, a flexible central core, tough ridges and beautiful looking sides to appreciate the delicate patterns of the hada.

Shihouzume Lamination - a specialty of Seki city using 4 different grades of steel forged and sandwiched into place to create the perfect balance between functionality and beauty

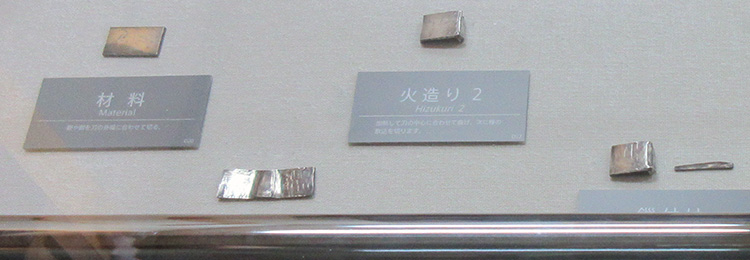

Shihouzume Lamination - a specialty of Seki city using 4 different grades of steel forged and sandwiched into place to create the perfect balance between functionality and beautyThe explanations are very detailed and take you through the entire sword making process, both of the blade and the highly intricate fittings which are a high art form in their own right, starting off with an explanation of the different grades of steel obtained from the Tatawara furnace - Japanese Tamagane steel, also known as Wako (Japanese Jewel Steel)..

The art of selecting each piece of steel, judging from its appearance, its weight, and a lifetime of experience and intuition is a true art in itself and not something that should be attempted by anyone except those who REALLY understand Japanese swords and have been trained exclusively in the use of this unique steel.

The demonstration has many videos available for anyone who is interested in more details, and while it is presented in Japanese it is mostly visual and easy to understand what is happening even if you are not able to understand Japanese.

And the displays are presented mostly in Japanese, but with enough English to understand the names and do your own research with professor google if something grabs your full attention and demands an immediate explanation.

The process of differentially hardening and tempering a Katana is what gives it the hamon, its harder edge and softer spine, and causes it to bend to its distinctive curved shape

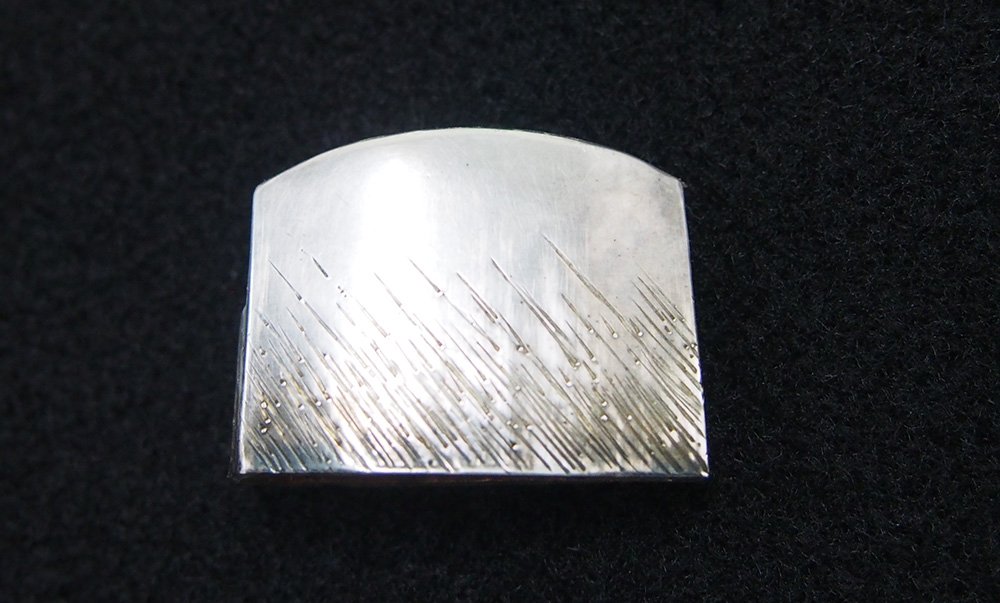

The process of differentially hardening and tempering a Katana is what gives it the hamon, its harder edge and softer spine, and causes it to bend to its distinctive curved shapePersonally, I was quite fascinated with the art that goes into making the humble habaki. Many were made with a base of copper that was perfectly fitted and custom made for one particular sword, and the base of copper was further wrapped in a jacket of silver or gold - making it no wonder that the base price for the simplest hand made habaki is between $300 to $1000 and goes up exponentially from there as only true handcrafted, one of a kind art pieces really can..

It takes a specialized artisan to make the habaki blade collar of a Katana. When you see how much is involved in the process, you begin to understand why..

It takes a specialized artisan to make the habaki blade collar of a Katana. When you see how much is involved in the process, you begin to understand why..Here is what one of the habaki looks like on one of the antique Samurai swords we got to disassemble and examine close up during this visit..

Example of a beautiful silver habaki from an antique Samurai Sword

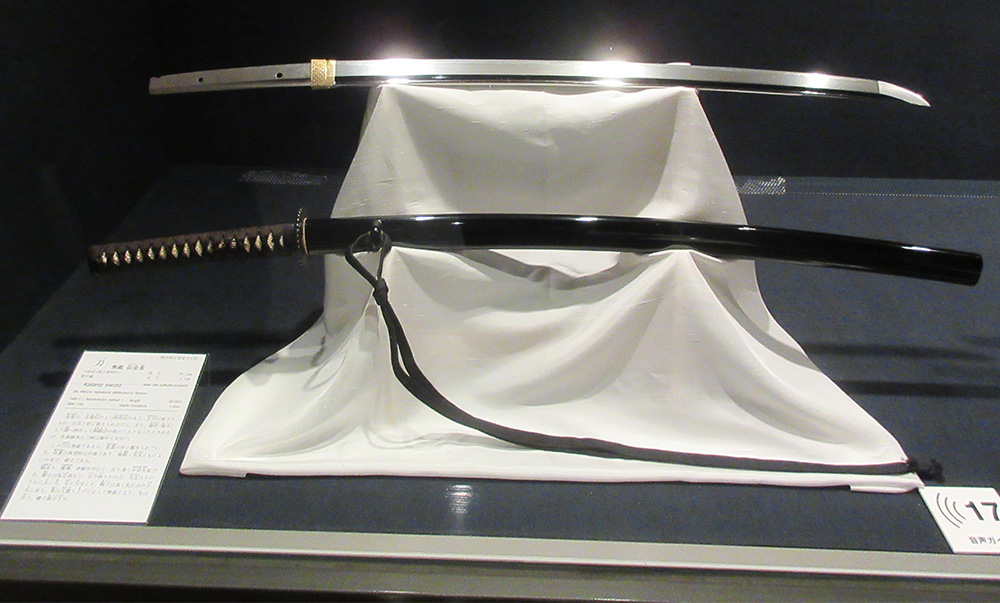

Example of a beautiful silver habaki from an antique Samurai SwordNaturally though, the real highlight of any trip to a museum with swords in it is to see the actual antiques themselves, and as you might expect the museum has no shortage of antique Samurai Swords, but also features the more recent restorative work of several prominent local artisans, many of which are given the status of national living treasure in Japan, and whose works are of such quality and such renown that if you need to ask how much, then you definitely cannot afford it..

Many of the swords here are priceless national treasures, for within the world of antique Samurai swords there are at least 5 levels of classification - and according to Japanese law, only swords that are from level one and level two may be exported from Japan - swords at level 3 and above can be owned privately but as they are considered to be national treasures can never leave Japan or be exported.. (and if they are currently overseas, should probably be returned and certainly not traded legally)..

Swords like, well - like these (click on an image to open the gallery):

Gallery

And for anybody who thinks if you have seen one you have seen them all, here are some antique Samurai Swords from the experimental Edo period that show not everyone was into the same style of fittings..

For example, THIS sword is clearly worn by someone who does not need to care about social conventions and has enough power and wealth to style their sword however the heck they want to!

Or one of my favorites styles, the sleek look of a rare Aikuchi Katana without any kind of tsuba - usually found not on antique Samurai swords but rather generally found on Tanto, but for every rule there is always an exception..

While getting to the museum is not easy without a car, the easiest way to go is via train from the nearest major city of Nagoya to Mino-Ota station, and then take the "Nagaragawa Testudo" Bus line directly to "Hamonokaikan-Mae Station" where there is a clearly signed 4 mins walk to the museum itself.

You can find out more information about the area by downloading this PDF area guide put out by the local council in English or this write up explaining when you can see actual live demonstrations like in the video below (by the smith I spent my time with - as we will get to in the next section).

Meeting the Tosho (master Swordmaker)

I was very fortunate to be taken by car to the museum in the company of one of the last remaining Japanese sword smiths who had dreamed of being a blacksmith ever since he was a child and who started his prestigious career at the tender age of 18 and has been making Japanese swords ever since - Kanemasa the 2nd, otherwise known simply as 'Shinsuke-san'.

A photo of Shinsuke and his Master, Kanemasa I.

A photo of Shinsuke and his Master, Kanemasa I.Shinsuke-san has been friends with a local long term US expat and resident of Japan, Chris Loeber, who contacted me a few months before the trip and through whom, I came to meet the smith and be fully immersed and introduced to the world of antique Samurai Swords.

We first met up and while Chris was busy teaching some English lessons, took a side detour to the local Shinto and Buddhist temple..

Before heading off for a local delicacy and a food we both had a shared love of, Hamburgers! In this case, a very delicious gourmet burger made by a gentleman who was formerly a French chef, but followed his passion and opened a humble burger joint selling some of the juiciest, most delicious burgers around..!

A Japanese French Chef's vision of a Gourmet Cheeseburger. And yes, it was delicious!

A Japanese French Chef's vision of a Gourmet Cheeseburger. And yes, it was delicious!At this burger joint we enjoyed one of many conversations - and in only a few short days I was able to dramatically increase my knowledge of antique Samurai Swords - clarifying many previously open and unanswered questions in minutes, and learning that some of the things that were taken as common knowledge among Western aficionados of antique Samurai Swords and the history of the Samurai in general.

For example, what in the west is known as a Ko-Katana is Wakizashi length blade with a Katana length handle - but to the Japanese, the Ko-Katana is half of a Kozuka knife set up (the blade part, Ko referring to a small or 'child' so the KoKatana is a baby sword with a Kozuka - small tsuka).

Tanto, Wakizashi and KoKatana - the blade of the Kozuka knife, not a short bladed Katana..

Tanto, Wakizashi and KoKatana - the blade of the Kozuka knife, not a short bladed Katana..As such, what we call a 'Ko Katana' in the west would be referred to as an O-Wakizashi..

And I also learned the importance of the Japanese measuring system when it comes to classifying antique Samurai Swords. It is actually very easy and clear, and it had to be in an age when only the Samurai were legally permitted to carry the Katana - but many wealthy merchants and non-Samurai wanted to arm themselves legally with a blade as close to a Katana as possible.

Thus, these are the lengths that separate each type of blade - measured in 'Shaku' (approx 11.9" or 30.3cm) which are divided into smaller units called 'Sun', 10 of which make a Shaku (and are in turn divided into even smaller units again known as 'Bu') divided as follows:

- Blade length of under 1 shaku (11.9") is a Tanto - measure from the back notch of the habaki collar (the 'Munemachi').

- Blade length of between 1-2 shaku (11.9 to 23.8")

- Blade length of over 2 shaku (longer than 23.8") is a Katana.

And I also learned that for the most part, the naked blade of a Katana's point of balance is almost always dead in the center, and it is only the fittings which shift the balance back towards the handle..And that the first few inches of a Katana are always unsharpened to start with when the sword is new, but gradually become sharp as the sword is re-polished time and time again.. (I always through that it was to prevent accidents when performing iaido, which may be partially true, but the unsharpened section is primarily used to gauge the swords newness - and is not a part of the sword that you cut with anyway..)

A new Katana always has the first few inches unsharpened to designate it as a new sword. As it is polished over time, this blunt area disappears.

A new Katana always has the first few inches unsharpened to designate it as a new sword. As it is polished over time, this blunt area disappears.Oh, and among other things, I also discovered for the first time a neat little carved piece of Honoki wood known as a tsunagi that is used in lieu of a blade to hold the fittings together while the blade is kept safely locked away in Shirasaya.

A wooden 'place holder' for a blade known as a Tsunagi. Even these are finely crafted..

A wooden 'place holder' for a blade known as a Tsunagi. Even these are finely crafted..Basic stuff for many more experienced enthusiasts, but for me these things really filled in many of the gaps in my knowledge and made me eager to learn even more..

But back at Shinsuke-san's forge, I quickly learned that I am not by any means a natural smith.. For I was fortunate enough to watch the Master himself in action, and not only that, to try my hand at forging a blade from Tamahagane!

Shinsuke-san at work in his forge

Shinsuke-san at work in his forgeHaving never forged anything before, I did my best to observe the technique Shinsuke was using - but unfamiliar with how much force was needed to shape the super heated steel and, forgetting the technique I had been shown and using my own weird method instead, tried my hand at forging a small pocket knife and got..

How to describe it? If it looks like a duck and it quacks like a duck..

Yes, instead of a knife I ended up making a duck but oh what a duck it was, for it was a steel duck with 'hada' - that unique folded pattern that formed the basis of the steel in every traditionally made Katana..

My first attempt at forging a knife produced - well - a duck..

My first attempt at forging a knife produced - well - a duck..This was rather unexpected and provided everyone with a good laugh. But it also had a deeper meaning, for in a sense it reflected the state of the Japanese Sword making industry and the domestic market in Japan for antique Samurai Swords..

If things keep on going the way they are, even making a duck like this will soon enough be a thing of the past..

Twilight of the Samurai Sword?

I had always imagined that sales of Japanese Nihonto and antique Samurai Swords in general was a vital and brisk trade and that sword smiths in Japan MUST be rich..

Boy was I in for a wake up call..

What I learned instead was that the Japanese sword industry, like the sword industry the world over, was not in a healthy state and that while a newly made Katana starts at around $7,000 - the smith doesn't get to keep much of that money..

Even a basic blade in Shirasaya requires the specialized input of a skilled polisher, who may charge $3000 to hand polish the blade, then there is $500 for a basic habaki and around $1500 for a hand carved Shirasaya and if it is a standard entry level Katana priced around $7,000 (with minimal fittings as described above) the smith is only taking home $2,000 per sword - and that is after the cost of steel, electricity, raw materials and any temporary labor he may hire to assist with the hammering.

Limited by Japanese law to make only 12 swords a year available for domestic sale and its clear that no-one ever got into making Katana for the money..

But the sad state of the Japanese economy, which has been steadily declining for the last 30 years or so, is now at a point where the few people in Japan who could previously afford a genuine Gendaito (recently made Katana, such as those Shinsuke-san makes) or antique Samurai Swords are no longer in a position to buy..

This was contrary to what I had seen and been told previously about the Japanese sword market - after all I had always heard that there are some 300 smiths registered with the Japanese government, which is as big if not bigger than Longquan in China.

But what I did not know that of those 300, only 10% are actively still making swords, the other 270 people are far too old now - and of those 30, few are able to afford to do it full time and there are no factories churning out swords like in China.. Even the central producer of components for iaito (unsharpened training swords with zinc alloy blades) only makes them on a 'on demand' basis and is a small, family owned company..

Tanking prices of antique Samurai Swords and non existent production of new swords made it all too clear - unless something changes very soon, we may well be witnessing the Twilight of the Samurai Sword made in Japan.

A brief stint selling antique Samurai Swords...

For many years, Japans declining economy and the increasing burden of an aging population have been impacting the sales of antique Samurai Swords. But by 2020, things had come to a head..

Domestic sales had almost entirely dried up, and desperate to keep going, several antique dealers in Japan had been looking to the West for sales - but were unable to make the vital connection..

This is where SBG entered the picture - for having the infrastructure already in place, and with sudden access to dozens of antique Samurai Swords at insanely discounted prices - well, it was a no-brainer..

We worked together for a while to try and offer these swords to new homes in the west, many being sold at ridiculously discounted pricing - though we faced some hard headwinds as the timing of our venture happened to coincide with the worldwide panic caused by the COVID-19 pandemic..

But even with this added level of challenge and complexity (especially with regards to shipping, which almost ground to a halt there for a while) we were able to offer some crazy good bargains to folk who were quick enough to snap them up (and quick they were, the best listings were sold in an hour or two at most)..

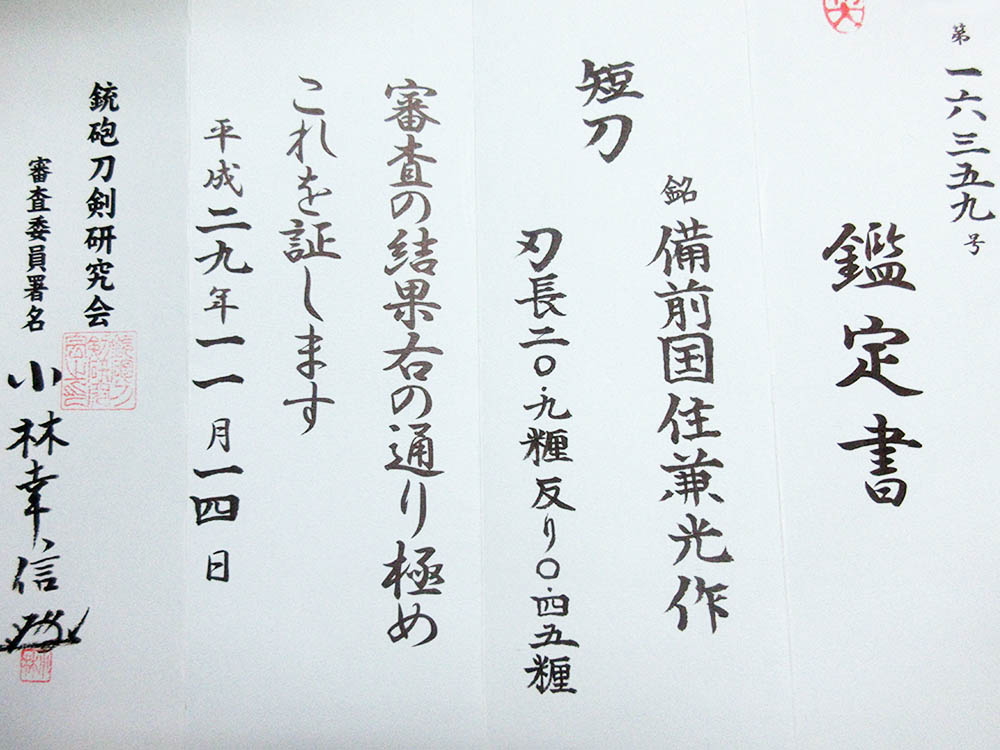

Above is such an example which in this case is a 700 year old antique made by a famous smith 'Kanemitsu' and verified as authentic by Kobayashi Yuhibonu from Juho Token Kenkyu Kai.

Tokubetsu Kicho Origami - a certficate of authencity by one of the many organizations charged with identifying antique Samurai Swords

Tokubetsu Kicho Origami - a certficate of authencity by one of the many organizations charged with identifying antique Samurai SwordsOrigami

No, not the art of paper folding, but rather the folded papers by the same name that certify a Japanese sword. The most prestigious are provided by the NBTHK (Nihonto Bijutsu Token Hozon Kyokai) - read more about what they do and the different types of certification they provide here in this article from Unique Japan.com and here in Richard Steins excellent Japanese Swords index

Normally a blade of this age in this excellent condition would sell for $10,000+ however we were able to offer it for just over half that price. And it wasn't just antiques that were discounted, even recently made Gendaito were available at a fraction of the cost they would need to have made new..

Case in point, below is a stunningly beautiful Gendaito made in 1994 that would again cost well over $10,000 to make if one was starting from scratch, but went out the door for a total sale price of less than $4K...

It truly was quite crazy - and it would appear that if you know where to look, you can STILL find bargains like this out there with these amazing pieces of Japanese history literally being sold off for pennies on the dollar..

While we are no longer currently involved with the antique Samurai swords directly, we know that there are still many thousands of antique and recently made Shinken out there - but it definitely begs the question, what is the future of the sword industry in Japan?

With very few people becoming sword smiths and most of the registered smiths now retiring or dying off, there is a very real danger that the art of making the Japanese sword could be lost in Japan..

But in the meantime, the tradition hangs on - and the bargain 'clearance sale' on Nihonto continues.

Conclusion

The SBG and Blades of Japan Team (from left to right): Chris Loeber, Shinsuke-san and Paul Southren

The SBG and Blades of Japan Team (from left to right): Chris Loeber, Shinsuke-san and Paul SouthrenBeing able to handle and examine so many antique Samurai Swords in such a short period of time and being immersed in the world of the Japanese Swordsmith was truly a privilege. As I said, I learned more in a week than I have studying Japanese swords for many years from afar, and I highly recommend that if you are able to visit Japan to take a side trip to Seki City, especially during the annual Knife show in October.

But for those of you who cannot go quite just yet, I hope that this article has gone some way towards sharing the experience with you.

MORE INFORMATION

There are quite a few excellent articles about antique Samurai Swords on the internet. Tameshigiri.ca has a comprehensive article about how to evaluate Nihonto on their site here and another great overview of how to select a Nihonto is provided by Unique Japan.com here '7 points to consider when choosing your Japanese Sword'

And of course, we always recommend Richard Stein's exceptional work in The Japanese Sword Guide for a 40,000 feet overview.

I hope this information on antique Samurai Swords has been helpful. To return to The Ultimate Guide to Authentic Japanese Swords from Antique Samurai Swords: A Personal Journey in Japan, click here

Buying Swords Online Can Be DANGEROUS!

Find the Best Swords in the:

Popular & Recommended ARTICLES

The ONLY true free online magazine for sword enthusiasts. Delivered once a month on the 1st day of the month, no filler and no BS, just the latest sword news & info delivered straight to your inbox.