Recent Articles

-

Christmas Sword Buying Guide 2025

Dec 03, 25 10:53 PM

Sword Terminology - Made Easy!

Learning sword terminology is like learning a whole new language. And this article could easily have been just another big glossary of sword parts listed in alphabetical order..

You know, the kind you try to memorize for a while, give up on, and then refer to when confronted with a description like The blade has a lenticular edge with a POB around 4 from the crossguard - and it feels they might as well have been talking in Klingon ..

Now if you want such a list, the best ones Ive seen so far are over here at Sword Forum International and also My Armory respectively.

BUT if you just want a quick and dirty walkthrough of the most common need to know bits of sword terminology then this guide is for you!

The Blade and the Center of Percussion (COP)

Lets start off with the blade, which is actually divided into two sections .

The part closest to the handle is called the forte which is sword terminology for the strong part of the blade. Naturally enough, this makes the forte the best part of the sword to parry or block with.

Conversely, the closest to the tip is the foible or weak part of the blade and was traditionally used for making fast cuts to soft tissue such as the hands and face.

Where the forte (strong) meets the foible (weak) is the Center of Percussion (COP).

While it sounds like a bit of unnecessarily complicated sword terminology, the Center of Percussion (COP) is simply the point that produces the least amount of vibration when struck against a target. As such its capable of delivering the most powerful blows, and is often affectionately referred to as the sweet spot.

To find a swords Center of Percussion, simply lightly bang your sword on something and observe which point vibrates the least!

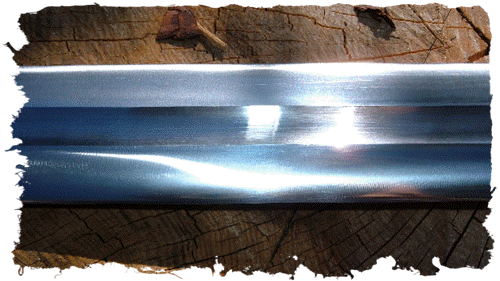

Some medieval style swords have what is called a central fuller running lengthways down the middle of the blade often mistakenly called a blood groove.

Contrary to popular fiction, the fuller is actually designed to lighten without sacrificing too much rigidity. But this extra rigidity only applies in the plane of the edge (e.g. when you cut something), and against torsion (e.g. when you twist the blade when cutting).

The fuller makes it lose some rigidity in the direction perpendicular to the flat (e.g. when you bend it with your hands).

The whole blood groove thing is the result of some 19th century sword terminology introduced by overly imaginative novelists!

Edge Angles and 'Geometry'

Naturally enough, the nature of the blades edge determines its intended function (e.g. practice, cutting or reenactment) and can accordingly be either dull, sharp or rebated.

The quickest and easiest way to sharpen up a dull blade is simply to file and polish away the steel until the edges meet up though if done just at the extremities like a knife it creates what is called a secondary bevel. On the other hand, when the blade slopes down smoothly from the central ridge - its called a single bevel.

If a swords edge is kind of in between a single and secondary bevel the correct sword terminology for this kind of edge is a lenticular or appleseed edge (which, as you might be able to guess from the word, kind of looks like the way the edges of an appleseed come together take a look next time you eat an apple to see what I mean!).

The opposite of a sharp edge is a rebated edge (also known as a blunt).

These specialized edges are suitable for safe re-enactment purposes and are nothing more rounded and blunted edges and tips designed to prevent the sword from cutting. (By the way, rebated swords are not just a modern invention and were used even occasionally used in medieval times during non-lethal fully armored knightly competitions).

BTW, for more information on how to sharpen a sword, check out my article about it here.

Point of Balance (POB)

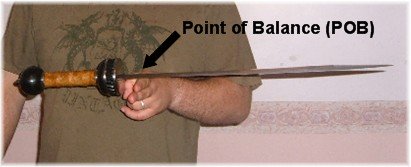

As we move down towards the hilt youll find the swords center of gravity, for which the corresponding sword terminology refers to as the Point of Balance (POB).

All this commonly misunderstood gem of sword terminology is referring to is the exact point where the sword will balance evenly on the back of your arm or across your fingertip and is typically measured by how far it is away from the crossguard.

It should be noted that there is no universal correct Point of Balance. The perfect point of balance varies depending on the swords weight, length, intended function and the personal preferences of the user

I know, I know a typical non-committal answer!

So just as a rough guide and to give you some idea, many people consider the ideal point of balance on a medieval longsword is from 2 to 4 inches from the crossguard. On a Japanese katana, a lot of people find that their preferred POB is from between 5 to 7 inches from the tsuba (hand-guard).

To find the point of balance on a given sword, simply balance it on your fingers (flat of course!) and measure from the guard.

Hilt and Tang

The Crossguard (hand-guard) is used as much (if not more) to stop your own hand from sliding down the blade when thrusting as it is to stop any blows aimed at your hand by an opponent.

In sword terminology the two arms of the crossguard are often referred to as Quillions.

The crossguard is also the first section of the swords Hilt, which also includes the grip and the pommel.

Just above the hilt, some swords (notably bastard swords, cut and thrust swords and some rapiers) have a Ricasso, which is sword terminology for small section of the blade which has been dulled to allow the index finger to grip it in a technique known as fingering.

The grip of a sword is where pretty self explanatory, and is usually a wooden, bone or ivory core that may or may not be wrapped with leather, bound wire or cloth.

At the very end of the sword we have the pommel (from the French word for apple) in other words that bulbous disc or knob of steel at the end that is used not only as a counterbalance but also as a grip for hand and a half usage.

Running through the hilt of the sword is the Tang which is basically the stem of the blade. Where the tang and the blade meet is called the Shoulder.

The best swords have a tang which is forged as part of the sword and is secured firmly to the pommel either by Peening (in which the tang sticks out the end of the pommel and is pounded flat) or Threading (like a screw, which is generally less structurally sound than properly a peened pommel).

Many swords made with the tang as a continuation of the blade are often mistakenly referred to as full tang sword. However a full tang sword actually looks like the handle of a kitchen knife, (e.g. a cross section of steel sandwiched between the handle on either side).

At the other end of the scale, most ornamental swords which have their own sword terminology such as Wall Hangers or Sword Like Objects (SLOs) - have a thin rod or rat tail tang which is welded to the blade as an afterthought and prone to stress breakage if wielded or used .

Conclusion

Now the basic guide above is a pretty good starting point and certainly a lot more helpful (I think/hope) than what I had to first wade through when trying to learn sword terminology for the first time.

But in reality, what is presented here is just the tip of the iceberg ..

My best advise to you is to read as many books as possible on the subject. Frequent the various Sword Forums. Check out the different glossaries when you come upon some unfamiliar terms.

And in no time at all what was once just meaningless gibberish becomes like a second language !

Speaking of a second language, Japanese Sword Terminology is doubly hard to learn. However, we did our best to put together a basic guide here - including tricks on how to remember the words and a pronunciation guide.

I hope this information on basic sword terminology has been helpful. To return to the WARNING: Do Not Buy Swords Online Until You Read This from Sword Terminology, click here.

Buying Swords Online Can Be DANGEROUS!

Find the Best Swords in the:

Popular & Recommended ARTICLES

The ONLY true free online magazine for sword enthusiasts. Delivered once a month on the 1st day of the month, no filler and no BS, just the latest sword news & info delivered straight to your inbox.